Under construction

![]()

Theodore Tin-Yee Hsieh

Department of Psychology

Judson University

The salient characteristics of the Chinese American churches have been closely related to changing immigration statutes. Perhaps, more than any other single factor, these statutes affected the historical formation of the unique character of Chinese America psyche and, by extension, the unique character of Chinese American churches. The Chinese-related immigration statutes enacted by the United States Congress in 1882, 1943, 1965, 1975, 1979, 1990, and 1992 will be used as benchmarks for discussion of the changes among Chinese American Evangelicals.

The early years of Chinese Americans were vague and sketchy. One California historian believes that the Chinese came to America before the Spanish and English.1 Another prominent scholar claimed that between 1571-1746 Chinese laborers were already employed in the shipbuilding business in Southern California.2 Yet another believed that the first Chinese laborer was not introduced to the Pacific Coast until 1788.3 But most students of Chinese Americans generally use 1850 as a starting point in their discussions of this highly visible, but relatively small ethnic minority group.4

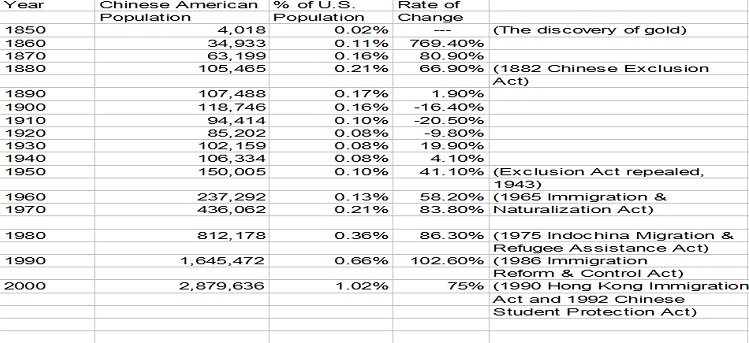

Because of their urban concentration and the exotic presence of Chinatowns in big cities, Chinese in America are quite visible. But, Chinese Americans are relatively small as an ethnic group, never numbering more than 1.02% of the total United States population. (Table 1 shows the trend of Chinese American population over the last 150 years).

Table 1 is adapted from the Chinese Population Trend provided by the Chinese American Data Center.5 For the 2000 Census, the definition of race includes multiple race categories. Chinese Americans include those who were one race only and those who had two or more races. The population of “one race only” Chinese Americans was 2,432,585 in 2000, representing 0.9% of the total American population.

The characteristics of the Chinese American population reflect the changing features of the United States immigration statutes. Accordingly, these major features are divided into four phases. Each phase reflects the unique characteristics of Chinese American churches also.

The Labor Immigrant Phase (1850-1943)

The Student Immigrant Phase (1944-1964) The Transitional Phase (1965-1988) The New Immigrant Phase (1989-Present)

1. The Labor Immigrant Phase (1850-1943)

The churches in the Labor Immigrant Phase were Cantonese-speaking, Chinatown-situated, and mission-centered.

The earlier immigrants were almost exclusively from Guangdong (Canton) province in south China who spoke a variety of Cantonese dialects. With the discovery of gold in California in 1848 and the need for workers to develop the American West, Chinese laborers from Guangdong province were recruited for these tasks. The sizable increase between 1850 and 1860 was evidence of this great influx.

In addition to the gold rush, Frederic Wakeman suggests that the Taiping Revolution (1850-1864) was another reason for the great emigration from south China.6 Led by Hung Sau Cheun, a Christian convert by Congregational missionaries in Canton, the Taiping Revolution mobilized millions of peasants to join his “Christian” political movement that included a ferocious anti-idol ideology. The revolution eventually costed between ten to twenty millions Chinese lives. People from the Guangdong area were forced to seek employment outside their own country because of the terror of war, famine and a series of natural disasters. These circumstances made them easy recruits for America’s Golden West. Cantonese was therefore the predominant dialect of Chinese American churches in the early decades of Chinese immigration until after World War II.Chinese immigration reached its peak in 1880 when Chinese constituted 0.21% of the total U.S. population, a percentage that would not be reached again until 1970. According to the U.S. 1880 Census, more than 75,000 out of a total of 105,465 Chinese in America lived in the San Francisco and Sacramento delta areas. In a single year in 1852, the San Francisco Customs House recorded more than 20,000 Chinese arrivals.7 In 1860, although the Chinese in America constituted no more than 0.11% of the total U.S. population, one out of ten people in California was Chinese.8 The concentration of this numerically small but physically distinctive ethnic group in one state might have contributed to the building up of anti-Chinese feelings in California.

As hostility toward the Chinese intensified, it became increasingly dangerous for them to live outside of Chinatown. The key event was the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. Many factors contributed to its adoption, but it is important to note that this act was the only exclusion against a special ethnic and national group in American history.9

This section will focus on the circumstances surrounding the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and discuss how this particular legislation contributed to the formation of a unique community pattern of Chinese Americans in that period.

While early Europeans made their Atlantic crossing for rather complicated religious, political, and economical reasons, the early Chinese pioneers crossed the Pacific for one specific purpose, economics. These Chinese laborers came to fulfill the dream that one day they would return home rich and secure. While Europeans burnt their bridges behind them, the Chinese had no intention of staying in this new country.10 In their early history in America, Chinese were also not encouraged settling down and staying.The early Chinese laborers toiled long hours for “coolie wages” which “White workers with families could not support themselves and for which even bachelors would not stir.”11 The panic of 1873 was slow in reaching the rich mining country of the far west, but finally its effects were felt. By 1875, it seemed to the white workers in California that no one but Chinese had jobs.

In 1877, soon after the great railroad strike, Denis Kearney, a recent Irish immigrant, organized some of the roughest of the unemployed in the San Francisco Bay area into the Workingman’s Party and the result was a campaign of organized violence against Chinese communities.12 In September 1885, a riot broke out in Rock Springs, Wyoming, in which twenty-eight Chinese were murdered and property valued at $148,000 was destroyed.13 In California, Chinese quarters were torched in Pasadena, Santa Cruz, San Jose, Oakland, Healdsburg, Napa, Merced, Yuba City, Petaluma, Truckee, Placerville, Chico, and Nevada City.14 This list indicates the rural and pioneer nature of the early Chinese immigrants. The riots drove them to the urban areas and forced them to develop a fortress mentality for self-protection, which remains until today. If riots did not do the job, government-enacted legal restrictions certainly succeeded in weaving a cocoon around the Chinese in America for the next 80 years.

Despite violent opposition and persecution on the West Coast, Chinese immigration reached its peak in 1882 with 39,579 arrivals.15 Ironically, it was the largest number of arrivals of Chinese in one single year. In May of the same year, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act forbidding Chinese laborers to enter the United States for the next ten years. Chinese teachers, students, merchants and travelers could continue to enter the U.S. and the Chinese laborers already here were assured of the right to leave and re-enter.16

But in 1888, Congress cancelled the right of re-entry with the passage of the Scott Act, closing the door to 20,000 Chinese who had temporarily left the country but who, at the time, had the right to return. The Scott Act of 1888 practically isolated Chinese in America.17 Most were afraid to leave the area where they lived. It is common to hear children of these early laborers tell stories of their parents who would stay for 40 or 50 years in one area in California. Although they talked about and thought about China everyday, they could never travel there because they were afraid they would not be allowed to re-enter the United States. Many of these old timers would not even set foot outside of California in order to avoid any legal complications. The isolationist mind-set led to a long period of mission-centered ministries in Chinatowns by various mainline denominations.

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was extended by the 1892 Geary Act for another ten years and was made permanent in 1902. The 1902 Act also denied Chinese the privilege of naturalization.18 In San Francisco today, Geary Street is a major east-west thoroughfare connecting established Chinatown on the Bayside to the newer Chinese residential Sunset district on the Pacific side. It is a daily reminder to thousands of Chinese Americans who travel on it of their exclusion from American life.

Psychologists look at aggressive behavior as “always a consequence of frustration.”19 The real issue rests in using prejudice and discrimination as aggressive weapons in inter-group conflicts. The conflict between the Workingman’s Party and Chinese laborers make a classical illustration in this case. Where two laboring groups are both being exploited, it often happens that the exploitation will generate conflict between the exploited groups. They either fail to see the real source of trouble or the more powerful group finds it expedient to attack, not the exploiter, but the other victims. Out of this conflict came the anti-Chinese agitation and out of the agitation came a racist ideology.20 From worthy, industrious, sober, law-abiding citizens, the Chinese rather suddenly developed into inassimilable, deceitful, servile people.21 Books with such titles as The Last Days of the Republic (1880) by Perton W. Dooner, A Short and Truthful History of the Taking of California and Oregon by the Chinese in the Year A.D. 1899(1882) by Robert Wilton, and Meat vs. Rice: American Manhood Against Asiatic Coolieism, Which Shall Survive? (1908) by Samuel Gompers and Herman Gustadt were influential in forming public opinion. Political and editorial cartoons had become an integral part of mass anti-Chinese hysteria.22

From a psychosocial perspective, the assimilation of the Chinese American population into the American mainstream has been difficult and painfully slow. In contrast, Miller documents “assimilation fears” on the part of white America as expressed by Congress and editorials in the national media on both coasts.23 For all practical purposes, in the past, the Chinese Exclusion Act functioned as more than a legal policy. It was a social traffic sign and a psychological barrier against integration. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was finally repealed in 1943, but the message had already been sent, especially to the predominantly Cantonese-speaking labor immigrants from Guangdong province and their American-born offspring.

From 1882 to 1943, the lifestyle and mindset of Chinese in America were more or less established. During this period, long in years but short in inter-generational memory, Chinese were denied citizenship, the right to present testimony in court, and legal protection in general. American citizens of Chinese ancestry were not allowed to bring their wives to this country. This prohibition created in Chinatowns a “bachelor society” for a long period of time.24 Even after 1943, the special restrictions continued. The Immigration Act of 1944 established an annual quota of 105 for persons of Chinese ancestry. This restriction and the uneven treatment between Chinese and European immigrants was a significant factor that delayed assimilation. The 1882 Exclusion Act based on ethno-cultural grounds was the first departure from America’s official policy of open, laissez-faire immigration.25 Its enactment and later amendments with further restrictions traumatically altered the psychic of Chinese Americans.

As much as factors of language and culture, this lack of legal protection drove many Chinese into a cocoon-like community and into a heavy dependency upon institutions such as “Benevolent Associations,” “family associations” and “Tongs” to regulate, police and intervene in their commercial, familial and social affairs.26 Whereas the ethnic organizations of other immigrant groups played their most important role in the lives of the first generation newcomers, the Chinese associations have continued to this day.27 The Chinese churches today, though more prosperous, are still in steep competition with the social and commercial organizations in Chinese communities. To discourage Chinese from becoming Christians, there was a popular saying among Chinatown establishments in early days, “one more Christian, one less Chinese.” This social pressure made many churches mere community centers. Even for many who attended various mission-churches in Chinatowns, their attendance was for social-communal reasons.28 They wanted to be seen in a place that connected them to the outside world. They dressed up in something different from their everyday work clothes. Since almost all mission-churches during this period were bi-lingual, services in English helped them feel that they were in America. Many parents also encouraged their children to attend church and be involved in children and youth activities, not for spiritual reasons, but for social and cultural exposure.29

The early Chinese churches in America were all mission-centered. Chinese churches traced their common origins to the home mission movement of various American denominations.30 A former medical missionary to China, Dr. William Speer of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions, obtained permission to work with the Chinese in San Francisco in 1852. His work initiated this home mission movement. The Speers were able to preach in Cantonese and by November 1854, the first Chinese Christian church outside of Asia was established with four former Presbyterians from Hong Kong as charter members. The Speers conducted a medical clinic in the mission and their successors continued their work and conducted evening and day schools to study English.31 Such activity became a prototype for all programs in Chinese churches. Even in Chicago, for example, an English class was initiated in 1924 by the prominent North Shore Baptist Church for the Chinese laundrymen in the area. It started out with 16 students and, by 1943, the class record showed over 100 in attendance. The class was taught by Mrs. Helen Blachley and her physician husband. Mrs. Blachley handed over the Chinese class to a group of 12 student immigrants who organized it into a church on October 10, 1959.32 Today, the Chinese Baptist Church of Chicago is a thriving independent church with over 300 people in attendance every Sunday and has its own building. Otis Gibson, a missionary to China, began his language work in San Francisco in the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1868. William Pond started his language classes under the sponsorship of the American Missionary Association of the Congregational Church in 1874. The American Missionary Society then established its work in 1870.33 By the turn of the century, there were ten Chinese churches and 271 Sunday Schools and missions active in the San Francisco area.34 In the minds of many of these early Christian workers, sharing the Gospel was not their only goal. They also wanted to “Americanize” the Chinese because, at that time, the predominant view in the country was that the Chinese culture was inferior and that the Chinese needed to be civilized.35 To be sure, workers such as Otis Gibson and William Pond believed that when the Chinese learned English, their heathen minds would be opened to the Christian faith.36 The attitude of contempt may have been formalized by experiences with labor immigrants here in the States and with the initial converts who were social outcasts in China.37 In spite of the burden of this attitude, Chinese American Christians grew in number and consistently stayed around 5% of the Chinese in America. 38Five percent was not a discouraging figure, considering that after 150 years of concentrated missionary work by some of the most capable and charismatic missionaries from the west, less than half of one percent of Chinese in China claimed to be Christians in 1949.39 Although some may view the western missionary enterprise in China as a failure, many converts during the missionary era would become key leaders outside of China in the succeeding phases of Chinese Christian churches.40 A case in Chicago illustrated the “success” that was to come. By the end of the Labor Immigrant Phase in 1943, one church (Chinese Christian Union Church), one mission (Church of the Brethren), and one English Bible study class (North Shore Baptist Church) existed for labor immigrants. Out of this humble beginning, there were four churches with a total membership of 450 in 1968, representing 6% of 7,500 Chinese in Chicago.41

The history of Chinese Christian Union Church in the heart of Chicago’s Chinatown illustrates the developmental characteristics of Chinese churches in America. In 1890, Presbyterian, Baptist, Congregationalists and Methodists joined the Federation of Churches of Chicago to establish a “Chinese Sunday school”, near Chinatown at Clark and Van Buren Streets. In 1912, the Sunday school was moved into Chinatown at 295 South Clark Street. At that time, Chinatown was split over “tong wars.” “On Leong Tong” was forced out and moved to Cermak and Wentworth Streets. The Sunday school followed, moved to 223-225 W. Cermak Street, and was renamed Chinese Church of Christ. In 1927, the church moved to its current location at 2301 S. Wentworth Street and continued to be supported by the American denominations through their home mission societies. When it became financially self-sufficient in 1945, it was also non-denominational and renamed itself the Chinese Christian Union Church to acknowledge its interdenominational heritage.42 In 2007, Chinese Christian Union Church is considered one of the most prestigious Chinese churches in America, holding worship services in Cantonese, Mandarin and English. It has planted two churches in the Chicago area and is in the process of planting a third one in 2007. Its youth and young adult ministries are vibrant. Its members have served as short-term missionaries all over the world. Over 20 of its former members are in full-time ministry. It also bought the architectural icon of any Chinatown in America, the huge former “On Leong Tong” building constructed in classic Chinese style, and converted it into an all-purpose community center for social services.

Although Chinese Christians in Chicago generally recognize 1890 as the beginning of evangelistic efforts among Chinese, the actual start was five years earlier. In 1885, H.J. von Qualen, a Danish immigrant to the U.S. who had never seen China, became interested in that country and its people. While attending the Scandinavian Department of the Chicago Theological Seminary, he visited Chinese laundries and recruited Chinese to the Sunday school class. Among the members of that class were Eugene Sieux and John Lee. In 1887, von Qualen began the very first foreign missionary activity of the Evangelical Free Church of America in Canton. Sieux and Lee became staunch Christians and, in a most unusual manner for that time, returned to China to become co-workers together with von Qualen. The 1888 testimony of John Lee demonstrated what had been uncommon but subsequently became a pattern for many: that many Chinese Christians in America gave up their professions to enter full-time ministry.

In the following year which is 1886 Brother von Qualen wanted to carry over the missionary work to Canton, China, and he requested me to go together with him, but I did not fulfill his request owing to my business is not yet settled.

A year after he again made up his mind to go to Canton, China, he alone so he went…. And in the year of our Lord 1888 Bro. von Qualen send a letter to the Committees of the Foreign Missionary Board requested me to come home to do the missionary work with Brother von Qualen. At that time I am still doing the little business in Chicago and the Committees come many times to my little shop with our Brother von Qualen’s request and they urge me to leave Chicago soon for Canton, China. In answer to the Committees called, I sell the business at once. Then I left Chicago for China at the ending of November at the time Brother von Qualen, Mr. Eugene Sieux and myself became preacher up to this present year which is thirty years now from hence.43

Through wartime friendship between the United States and China and pressure from various groups, Congress repealed the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act on December 17, 1943.44 With the annual immigration quota set at 105 for persons with Chinese ancestry in the Immigration Act of 1944, the repeal had far less effect than expected. However, the repeal did signal the beginning of the Student Immigrant Phase of Chinese American churches.

2. Student Immigrant Phase (1944-1964)

The main event that made these twenty years the Student Immigrant Phase was the Communist take-over of mainland China in 1949. Many students, scholars, highly educated businessmen and politicians were stranded in the United States and were allowed to stay. Many more who had escaped the Communist regime on mainland to Hong Kong, Taiwan and the south and south-east Asian countries were allowed to enter America through a host of special legislations to be discussed in this section. Because these immigrants tended to be highly educated, it might be appropriate to call them “Student Immigrants” as compared the “Labor Immigrants” discussed in the last section. As a rule, the labor immigrants did not have the opportunity to receive formal education in China.

Almost immediately after Japan’s surrender to end World War II on August 14, 1945, a brutal civil war between American-backed Nationalists and Soviet-backed Communists broke out in China. After lengthy fighting and much political maneuvering, the Communists won and established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949. The Nationalists retreated to Taiwan in December, 1949 to continue as the Republic of China (ROC). Both sides claimed to be the sole legitimate government of China.

Basically, the loyalty of Chinese Americans stayed with ROC whose two long time leaders, Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek, were Christians. ROC continued to represent China in the United Nations until October 1971, when it was ousted by the world body. The “China seat” in the U.N. was transferred to the PRC. America continued formal recognition of the ROC until President Jimmy Carter announced that after January 1, 1979, the United States would only recognize the PRC. However, Congress immediately passed a bill guaranteeing future defense of Taiwan and the continuation of trade and other relations through an American Institute in Taipei, housed in the former American Embassy.45

Since its founding in 1949, People’s Republic of China was a closed country. During the Labor Immigrant Phase, there were many Chinese who came to the United States as college students, visiting scholars, businessmen, tourists and diplomats. Their stays were short and they would return to China upon completing their proposed length of stay. But the Communist take-over of Mainland China in 1949 changed everything. Those who were already in America decided to stay because of their anti-Communist leaning. And the United States Congress passed several immigration laws that allowed them to stay as political refugees. Many others, who were still on the Mainland, realized that their futures were not in China. Often in great haste, these political bureaucrats, accomplished professionals, and successful businessmen packed their families and left the land of their ancestors. Most of them moved to Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore or Malaysia.46

Many came to America. Again, changes in immigration statutes played key roles in changing the composition of the Chinese population in America. The 1948 Displaced Persons Acts, the 1953 Refugee Relief Act, the 1957 Refugee Escapee Act and the 1962 Presidential Directive all were designed to allow these anti-Communist elites to enter the United States during the height of the Cold War era. For example, John F. Kennedy signed a presidential directive on May 23, 1962 to admit specifically from Hong Kong, the China-born Chinese who escaped Communism in the 1950’s. By 1965, 15,111 of them arrived in the United States. Among them were a significant number of intellectuals and business elites and their children.47

Meanwhile, many children of those who escaped Communism by moving to Taiwan reached college age. Nothing was more coveted by these high-achieving families than an admission notice from an American university. They sent their children to America in large number in the 1950’s and 1960’s, making Chinese the largest group of international students on most American campuses. These college students also represented some of China’s most intellectually capable and scientifically well-taught children.48 They joined the older professional refugees who were already in the country. Among them, five would become Nobel laureates in sciences. Their work-ethic and academic achievement would earn their generation the “Model Minority” label, a label received by them with mixed feelings.49 This was the second phase of Chinese American churches, the Student Immigrant Phase.

Four characteristics differentiated the student immigrants from the labor immigrants in the earlier phase. First, unlike labor immigrants, the student immigrants did not settle in Chinatowns.50 Instead, they found their way to racially mixed neighborhoods in the cities and suburbs around universities and research centers. Although most came to America under refugee statutes, they viewed themselves more as intellectuals. This change created a paradigm shift in the Chinese American churches, freeing them from the Chinatown-situated ministry.

Second, they did not have the fortress mentality of the labor immigrants fostered by years of exclusion and fears. Although they were raised as social and cultural elites in China, they were less interested in preserving their Chinese heritage than the labor immigrants.51 They became acculturated quickly in their mixed environments and were eager to raise their families as Americans. In Chinese Americans this change raised the expectation in church administrative styles, quality of preaching, and the educational credentials of the ministers.

Third, Cantonese was not their main dialect. Many of them grew up in Mainland China or homes in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore or Malaysia that spoke Mandarin. In fact, many of them could not converse in Cantonese. Cantonese-dominated Chinatowns almost seemed foreign to them.52 Many churches began to move from bilingual to trilingual, using English, Cantonese and Mandarin in their separate services. Smaller churches had to decide whether they wanted to be an English/Cantonese church or an English/Mandarin church. Many Cantonese-speaking Chinese conversed in English with Mandarin-speaking Chinese. Mandarin did not become the language of choice for a majority of Chinese churches in America until the 1990’s.53

Fourth, whereas very few labor immigrants came to America with any Christian background, many student immigrants came either as Christians or had prior contacts with Christianity. Numerous students had been educated in colleges and schools established by American missionary and academic organizations. Depending on their prior experiences, some either joined the existing Christian groups or became quite out-spoken in their criticism of the church. Large groups of experienced Christians from Hong Kong, for example, literally transplanted in a wholesale manner their church activities, hymns and sermons from home. Chinese pastors from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and other Southeast Asian countries were invited to fill pulpits created by new churches as well as by the old but changed churches. The socio-economic positions and leadership skills of both these pastors and laymen led to several significant changes in Chinese American churches in the 1950’s and 1960’s.54

Most significantly, the Student Immigrant Phase practically saw the end of denomination-sponsored missions among Chinese Americans. Before 1943, almost all the Chinese American churches were located in Chinatowns in large cities and were financially supported by American denominations with varying degree of autonomy. A number of these churches were staffed by western ministers whose sermons were translated word for word into Cantonese. Many of these mainline denominations were also known for their liberal theology, which did not sit well with many Christian student immigrants from Hong Kong, who were from evangelical/fundamentalist churches. With their leadership skills and financial resources, they were able to establish new churches or move existing ones into independent status and make them more conservative theologically. The history of two prominent churches, one from the west coast and one in the Midwest, illustrate this change.

Cumberland Presbyterian Chinese Church, located in the heart of San Francisco Chinatown, began as an English class in the home of Mrs. Naomi Sitton in 1894. Mrs. Sitton was sent to Chinatown as a missionary by the Women’s Board of Missions of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Although it grew in the next 60 years and became a major Chinese church in San Francisco, it continued to be known as the Chinese Cumberland Presbyterian Mission until 1961 when it received its charter and changed its name to Cumberland Presbyterian Chinese Church. This change set the stage in 1965 for the church to hire a graduate of Fuller Theological Seminary. This Hong Kong-born evangelical pastor led the church for the next 23 years, nurturing a church of 150 with only one bilingual Sunday service to a church of over 900 with six Sunday services in three different languages.55

Chinese Christian Union Church is the largest Chinese church in the Midwest and is the only church in Chicago’s Chinatown. It was started as a mission station in 1890 by several mainline denominations and developed later as Cooperative Christian Church for Chinatown. Through the leadership of some very capable laypersons, it was able to achieve financial self-sufficiency in 1945 and became a non-denominational church. As it became self-supporting, it moved into a newly built sanctuary in 1951, constructed a new educational wing in 1961, planted one daughter church in the south side of Chicago in 1984 and another daughter church in a northern suburb in 1986. All these accomplishments were achieved under the stable leadership of two prominent pastors transplanted from Hong Kong.56 Significantly, these two pastors were members of the Southern Baptist Convention, in contrast to the historical roots of this church in the more liberal mainline denominations.

Another significant change was the rise of non-denominational independent churches and para-church ministries during the Student Immigration Phase. Several key Chinese evangelical leaders were important in nurturing this change. These leaders were educated and established in China but were forced to leave the Mainland in 1949. Eventually, many of them came to America and moved naturally into leadership positions among the transplanted student immigrants during the height of the Cold War era. Charismatic, strong-willed and independent in spirit, these leaders were anti-Communist in their politics, visionary in ministry, conservative in theology and lifestyle, and very capable. They certainly made their influence felt during these developmental years of student immigrant churches. More importantly, they were most responsible in establishing the pattern of the Chinese American churches evident today: overwhelmingly conservative and generally independent. Even churches with denominational ties were not very denominational in orientation. The impact of six leaders during the Student Immigrant Phase (1944-1965) illustrates these changes.

Andrew Gih (1901-1985) was a leading evangelist in China for years before he moved his huge “Evangelizing China Fellowship” work from Asia to America in the early 1950’s. His organization was responsible for establishing over a dozen churches in America, and his rallies from one American city to another in the 1960’s and early 1970’s were major events among Chinese Christians.57

Calvin Chao (1906-1996) began his ministry among college students as executive director of Intervarsity in China and moved his work after 1949 to Hong Kong. He moved his family to Singapore in 1951 and founded the Singapore Bible Seminary before migrating to the United States in 1956. He established Chinese For Christ Fellowship and worked among the student immigrants. He led and nurtured Bible study groups on university campuses throughout the country. He later helped students and scholars establish their own churches when they moved to other cities after graduation. Major university cities, including Berkeley, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York and Seattle still have large and thriving Chinese For Christ churches. 58

Moses Yu (1928- ) came to America after Intervarsity work in China. A man of vision and entrepreneurial skills, he published a popular bilingual hymnal when the expanding Chinese American churches were in need of a more modern hymnbook. Later, he published a Chinese-English Bible that today is still the number one selling bible among Chinese Christians worldwide. These were not just business successes. They filled the spiritual and organizational needs of the churches. Rev. Yu was also the first to see in 1964 the need for a Chinese-speaking seminary in America, anticipating the center of Chinese evangelicalism’s shift to the United States. Christian Witness Theological Seminary was established in Berkeley, California, and its graduates can be found serving in churches coast to coast. 59

Ted Choy ( -1992) and Moses Chow (1925- ) recognized the potential of reaching Chinese students and scholars in America while working with International Students, Incorporated, in the 1950’s. In 1963, they co-founded Ambassadors for Christ, Inc., which became the most influential Chinese evangelical Christian organization on college campuses. They organized large college conferences and retreats, campus Bible study groups and nurtured many of them into campus churches. Moses Chow also organized a key east coast church in 1962 that was studied in depth by sociologist Fenggang Yang in a ground-breaking book.60

Thomas Wang (1925- ) established the Chinese Christian Mission (CCM) in Detroit almost as soon as he came to America in 1958 as a student immigrant. He is “movement” oriented, interested in revivals and societal changes. He left CCM in 1975 to become General Secretary of Chinese Coordination Center of World Evangelism in Hong Kong and later, as International Director of the Lausanne Committee for World Evangelization. After that, he became International Chairman of the AD2000 and Beyond Movement. His most recent involvement is the founding of the Great Commission Center, serving as its president. The publication in 2006 of the mass-mailing magazine, America, Return to God, perhaps illustrates best his ministry. He has mobilized significant number of Chinese American Christians to get involved in missions before and now he is calling them to urge their country to turn back to God. He is a mover and he is in the business of renewal and revival. 61

Demographically, the Student Immigrant Phase saw the continuing decline of the male-female ratio within the Chinese American population. From a high of 26.79 males for every female in 1890 to 14.30 to 1 in 1910, 3.96 to 1 in 1930, 1.90 to 1 in 1950, and 1.11 to 1 in 1970.62 Interestingly, Chinese American Data Center figures showed that for 1990, there was a slight male deficit in the country. There were 821,542 males to 827,154 females. Times had changed. With a balanced sex ratio, young adult activities in student-immigrant-oriented churches became very attractive and consistently had greater participation than all other community groups.

There was also a time in the 1960’s when some church leaders in Chinese American circles began to believe that the days of Chinese language ministries were numbered. There was tension within churches about the primary language, English or Chinese. There were debates, heated at times, at all levels of church meetings about the necessary modifications of ministry priority. Should the church continue to focus on the first generation Overseas-Born Chinese (OBC’s) or direct its resources to the American-Born Chinese (ABC’s)? 63 Indeed, the proportion of foreign-born Chinese in America had certainly declined from a high of 99.8% of OBC’s in total Chinese American population in 1870, to 90.7% in 1900, to 48.1% in 1940, and to a low of 39.5% in 1960. Not only the children and grandchildren of labor immigrants were English-speaking, but the recent student immigrants and their children were speaking English more and more and speaking Chinese less and less. The 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act ended the debates in Chinese American churches. The percentage of foreign-born Chinese Americans rebounded to 46.9% in 1970 and to 63.3% in 1980. In 1990, a drastic change occurred. The balance shifted to 506,116 for the native-born and 1,142,580 for the foreign-born. Chinese language ministry, especially in the Mandarin dialect, became all important. The immigration statutes again played a significant role in altering the programs of Chinese American churches.

3. The Transitional Phase (1965-1988)

On October 3, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Hart-Celler Act into law, abolishing racial discrimination in American immigration statutes. It was a significant day for Chinese Americans because, for years since the repeal of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943, only a token of 105 Chinese could be admitted as immigrants under the established quota. This quota did not simply include someone from China but anyone with at least 50% Chinese ancestry from anywhere in the world. 64 Although many Chinese were admitted under previously mentioned special statutes as political refugees or people with special skills and talents, the number of Chinese immigrants up to 1965 was small. The 1965 Hart-Celler Act raised the Chinese quota to 20,000 a year, equal to quotas for every other country. In addition, spouses, parents, and unmarried minor children of U.S. citizens could enter as non-quota immigrants. The impact of this new immigration statute on the size of the Chinese American community was immediate. The Chinese American population in 1960 was 237,292 (0.12% of the general population). After the Act, the size of Chinese-American population almost doubled to 436,062 in 1970 (0.21%). It doubled again in 1980 to 812,178 (0.36%), in 1990 to 1,645,472 (0.66%), and in 2000 to 2,879,636 (1.02%).

The impact of the 1965 Act on Chinese Americans was not just in number but also in psychic. The tenor of the Act made them feel equal to other Americans. It also helped them acquire a much needed sense of belonging. For decades, Chinese, especially Chinese Christians, had been wandering in Southeast Asia without any sense of being rooted. Natural disasters, famine, political unrest, Japanese invasion and the Communist takeover of Mainland China had forced many Chinese to escape to the Philippines, Indochina, Malaysia, and Indonesia to a life of Diaspora. Even for those who moved to Hong Kong, a sense of transience persisted in that British Colony. This sense of transience was greatly accentuated after the 1966 “Red Riot” instigated by pro-Communist locals in concert with the beginning of the “Cultural Revolution” (1966-1976) on Mainland. The stability of American political and economic systems made it very attractive to a people who had experienced so much instability.

During this period, many more ethnic Chinese came to America under the 1975 Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act. In this group was a large contingent of Chinese Christians and Missionary Alliance pastors, missionaries and key lay persons. They joined forces with their Alliance colleagues from Hong Kong to organize over 70 churches in the next two decades. 65 The 1979 Taiwan Relations Act raised the yearly quota to 20,000, contributing to the sizable increase not only in the Chinese American population but also in their financial and organizational wherewithal. The 1986 Immigration Reform Control Act further legalized 13,752 Chinese already in the United States. As a result, there was a critical mass of Chinese American evangelicals in the New York City, San Francisco, and Los Angeles metropolitan areas. During the 1970’s and 1980’s, ministries, not just new churches, mushroomed. The Transitional Phase of Chinese American churches was a phase of maturing and significant psychological change.

4. The New Immigrant Phase (1989-Present)

The 1990’s was a decade of great growth in number and quality for the Chinese American community. Again, two acts passed by Congress were responsible for accelerating this growth. First, the 1990 Immigration Act raised quotas for Chinese from Hong Kong from 5,000 per year to 10,000. Second, the 1992 Chinese Student Protection Act allowed 52,425 students and scholars already in America to stay permanently as political refugees as a result of the Tiananmen Square “incident” on June 4, 1989.66

Since the 1970’s, with limited natural resources, enterprising Hong Kong Chinese created one of the financial centers in the world. It also became the global center for Chinese evangelicals. First generation leaders who moved to Hong Kong to escape Communism in the 1940’s and 1950’s planted a solid foundation for the future. They planted hundreds of new churches to accommodate new refugees. They created seven major seminaries and countless magazine and publishing houses. The prosperity of the evangelical Christians and their churches rivaled the prosperity of the business sector in Hong Kong. As Hong Kong business people began to invest in expanding China and global markets, including significant purchases of major cell phone company in Europe, airlines in Canada and container ports at both ends of the Panama Canal by one single Hong Kong company, evangelicals from this British Colony also started to spread their evangelistic and church planting efforts overseas. Chinese churches in America began to grow in number and size in the 1980’s. 67

In spite of her prosperity, Hong Kong is a city with limited jobs and career opportunities. As many Hong Kong families send their children overseas for education, they also encourage them to stay in those locations after graduation. They do so to establish a “beachhead” for the family in case they must evacuate some day from Hong Kong for social or political reasons. Many become “reluctant exiles.”68 Some of the most talented and devoted young Christians are among these “reluctant exiles”68 in America. They have played an important role in changing the landscape of Chinese American evangelicals.

Although many Hong Kong immigrants were reluctant at first, they no longer are reticent as a result of the events surrounding 1997, the year the British turned over Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China. The psychological change is greater than the actual political hand-over. For various reasons, many people in Hong Kong have lost faith about her future although China has promised the former colony that “everything” will stay the same until 2047. Many evangelical leaders planned their exit from the colony even before 1997. For example, Jonathan Chao, a founder and former dean of China Graduate School of Theology in Hong Kong in the 1970’s, moved his influential Christianity and China Research Center from Hong Kong to Taiwan in 1995 to avoid political complications.69 Since 1997, many other denominational and non-denominational ministries have made plans to shift their focus to America without moving their headquarters. Recently, Overseas Theological Seminary, one of the most important seminaries in Hong Kong since the early 1960’s, relocated to San Jose, California. The global center of Chinese evangelicalism is moving out of Hong Kong to America.

Hong Kong Chinese and Chinese Christians have moved to America in greater numbers since 1990, and churches and pastors have followed. By August 2005, there are 56 Chinese churches within the city of San Francisco, 25 in Palo Alto and the Mountain View area, 40 in the San Jose, Cupertino and Saratoga area, and 59 in east bay around Oakland and Berkeley for a total of 180 churches.70 The number of churches in each of these areas reflects the relative concentration of the Chinese population. According to Census 2000, there are 428,926 Chinese Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area, making it 0.42 churches per 1,000 persons. According to a 1980 study of Chinese churches in both Canada and the United States, the ratio was 0.47 churches per 1,000 Chinese, compared to 0.12 in Hong Kong, 0.14 in Taiwan, and 0.74 in North American churches in general.71 The increase in the number of Chinese churches seems to be growing at the same pace as the dramatic increase of the Chinese American population in the United States since 1965.

The increase is not just limited to the number of churches. The ministries of para-church organizations among Chinese American evangelicals have also become quite extensive. In the Greater San Francisco Bay Area, there are 65 ministry organizations listed in the directory published in the Herald Monthly.72 Included in this directory are five Chinese-language seminaries, eight music-related ministries, and twenty evangelistic organizations. The diverse nature of many of these churches and ministries may also reflect a lack of cooperation among Chinese American evangelicals. To paraphrase what is often said about people with diverse partisanship: when you have four Chinese Christian leaders in a gathering, you have five different organizations. Independent spirit, non-denominational mindset, and ministry passion are alive and well among Chinese American evangelicals.

For China and Chinese everywhere, 1989 was a pivotal point in history. The death of thousands of students demonstrating for democracy in Tiananmen Square on June 4th fomented deep soul searching as never before among Mainland Chinese intelligentsia and business elites brought up under the atheistic Communist regime.73 With Communism’s sociopolitical promises broken and personal hopes vacated, the Christian Gospel received a hearing from and a close examination by Chinese students and scholars and the general public. Upon accepting the annual Mann Prize in Media and Culture in 2003, a well-known Chinese American musician, originally from Mainland, recalled her spiritual journey in the following way:

It was the sound of guns of “June Fourth” that woke me up, making me see clearly the crimes of Communist totalitarianism. It was the countless lives of youth that died that shocked my conscience… My own search finally led me to a theme that is eternal--that God treasures every single life.74

Hundreds and thousands of talented Chinese elites became Christians, among them several on the most-wanted list as leaders of the Tiananmen survivors. Yuan Zhiming was a well-known intellectual in China. He was once an officer in the People’s Liberation Army and an editorial writer for People’s Daily, a government mouthpiece. As he used his writings to promote democracy, he became a target for arrest. After his escape to America in 1989, a group of Chinese Christians witnessed to him when he was at Princeton University. Soon after, he was baptized as a believer in August 1990. After studying at Reformed Theological Seminary in Mississippi, he has now become one of the most sought after speakers and writers in Chinese American churches today.75 Though less dramatic than Yuan Zhiming, thousands upon thousands of students and scholars from China have become believers and have joined evangelical churches. Their number transformed Chinese American churches overnight. Church after church report that Mainland Mandarin-speaking immigrants make up over 50% of total attendance.

The demographic data seem to support casual observations. The 1990 Census shows that the numbers of foreign-born population from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong are 530,000, 244,000, and 147, 000, respectively.76 The 1990 Census also reports comparisons in annual median income, with Chinese from China at $30,597, from Taiwan at $38,966, and from Hong Kong at $42,033.77 A Chinese pastor commented in 2004 that he had the impression that Cantonese-speaking churches paid their pastors better than Mandarin-speaking churches. Although these income data are from 1990, the disparity may have continued and may have some effect on the compensation disparity, if true, between Cantonese-speaking and Mandarin-speaking churches.

As a result of the growth of Mandarin-speaking Christians, new churches have been established and many Cantonese-speaking churches have added Mandarin services and hired Mandarin-speaking pastoral staffs. Churches have organized monthly Saturday night meetings to reach out to students, business people and visitors from the Mainland. Typically, a church treats these meetings as its major evangelistic ministry. Church members plan these meetings carefully and diligently invite target people. Meetings start with a free Chinese dinner followed by a short talk on practical matters such as auto repair, health insurance, childcare, immigration regulations or money management. The main event is usually a testimony from well-known scientists, writers, or business executives who share their spiritual journeys and how they converted from atheism to Christianity. Frequently, these speakers focus on topics such as the existence of God, conflict between creation and evolution, the meaning of life, the harmony of Chinese thoughts and Christianity or the difference of eternity faced by believers and non-believers. Judging by the conversations with and writings by Mainland Chinese Christians, many of them began their Christian journeys in these specially designed meetings.

Soon after their conversion, many of these Mainland Christians—scientists, professors and businessmen—report the urge to enter the full-time ministry. Most of them are married with families. All have promising careers ahead. But they decide to respond to the call from God and, with the blessings of their spouses in most cases, make drastic career changes. In the fall semester of 2001, for example, there were over 50 Chinese students at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Illinois. Almost all of them went there with prior professional experiences. Nine finished their Ph.D. studies before beginning their theological program. At the Overseas Theological Seminary in San Jose in 2003, a medical school professor from Wisconsin finished his M. Div. Program and embarked on a full-time evangelistic and writing ministry. These are mere anecdotes, but they do illustrate the source and quality of current Chinese American Christian workers. With their unique backgrounds, they often approach ministry with fresh insights and have a unique burden for the Chinese on the Mainland. Their connections there offer them greater flexibility and potential effectiveness. The following ministries may be used as an example.

Christian Life Quarterly was founded in 1997 in Deerfield, Illinois, by a group of recently converted Mainland Christians.78 It effectively acts as a bridge between its readers who grew up in a religious vacuum and historical Christianity with a past as well as a future. It uses historical paintings with Biblical themes on its magazine covers. It publishes articles dealing with historical theology, Bible difficulties, life issues, and controversies between China’s State controlled Three-Self church and the illegal underground house churches. Featured in every issue are personal testimonies by believers who have experienced religious persecution in Mainland China. Its theology is orthodox, its identity is evangelical and its focus is on practical faith. In many ways, this magazine provides a critical series of thumbnail pictures about this new majority of the Chinese American Christians: their mindset, concerns and aspirations. For example, the Quarterly started out as magazine, but its staff soon branched out by organizing all night prayer vigils on behalf of persecuted believers on the Mainland. These vigils attracted interdenominational participants from all over Chicago. It also organized several international conferences in Chicago with speakers from Hong Kong and China’s underground house churches.79 Whereas many other Chinese Christian leaders are afraid to offend the Three-Self Patriotic authorities in China. Christian Life Quarterly seems fearless in this regard.

Christian Life Quarterly and its publisher, Christian Life Press, takes on a rather intellectual approach in its ministry, engaging in apologetics and being unambiguous in its critique of governmental restrictions on religion in China and in its support of the underground house church movement. In contrast, the Chinese Christian Herald Crusades, Inc. in New York City takes a different approach. The Crusades, organized by a group of transplanted Hong Kong Christians, publishes the Herald Monthly with a worldwide monthly circulation of 412,900.80 General public and Chinatowns are its focus. There are no controversial matters. Its articles are meant to provide helpful insights to life in Diaspora with a Christian perspective. It presents one theme a month. Recently, for example, “Parenting Children as Immigrants” was the theme for one issue and “Depression in Immigrant Community” was the other. Its free copies are placed in newsstands in Chinese restaurants and super markets by its army of volunteers in big and small cities. It is printed attractively in five colors in a ten-page newspaper format and is usually picked up within days. In 2004, the Chinese Christian Herald Crusades added a sister publication, Delicacy of Life. It is a part of a new ministry to reach the Chinese restaurant workers. The restaurant ministry organizes socials and Bible studies at midnight for this large and largely neglected population. Although Christian Life Quarterly and the Herald Monthly are printed media, the readers can almost hear the Mandarin spoken from the Quarterly’s pages and the Cantonese from the Monthly’s columns. These two church-wide and worldwide publications reflect the current state of Chinese American evangelicals: the energized passion and gifts in reaching out to both the intellectual substance and the practical utility of the Christian faith.

Several observations may be made concerning Chinese American churches. First, overwhelmingly their identity is evangelical. Most of their ministers received theological training in evangelical seminaries. If these pastors were not seminary-educated in Hong Kong or Taiwan, most likely they were educated at Dallas, Fuller, Talbot or Trinity. The outside programs they adopt for use in their churches tend to have solid evangelical credentials. Promise Keepers, Focus on the Family, Creation Science, and Prison Fellowship have been popular choices for many years. In recent years, the book Purpose Driven Life was chosen by many churches for their small groups. One San Francisco area church prominently painted the “Five-Purpose” statements in both Chinese and English on wooden posts in the church parking lot. Another church used Rick Warren’s book for three successive years in their weekly adult groups.

Second, Chinese American churches are basically independent. This is not to say that there is no denominational affiliation. But the denominations generally exercise no significant control over them. Two groups of Chinese churches in America have strong denominational identity because of the close relationship the pastors and church members had when they were in Hong Kong. They are continuing their historical connection by establishing their own associations for fellowship and mutual support here in the United States. The Chinese Southern Baptist churches, numbering over 160 in America, and the 70 Christian and Missionary Alliance churches have such ethnic associations. Their associations are testimonies to the lasting legacy of the good work done by the missionaries from the Southern Baptist and Christian and Missionary Alliance denominations in south China. Still, there are some exceptions. In the Chicago area, there are five Chinese congregations associated with the Evangelical Lutheran Churches in America (ELCA). They have a closer relationship with their denomination than most other Chinese churches. The Hyde Park Christian Reformed Church is the fourth oldest Chinese Church in Chicago. It has one of the closest denominational ties. In general, churches with close denominational ties tend to be small. The larger ones retain the denominational names for historical reasons. Some simply changed their names to reflect the non-denominational status. Several years ago, the Chinese Brethren Church of Oak Park near Chicago changed its name to Chinese Bible Church of Oak Park.

Third, Chinese American churches are very “light” on diversity. Evangelical Chinese churches, in particular, are not only mono-ethnic (they are all Chinese all the time); they are also mono-dialect (one dialect at a time). Even within a single church, Mandarin, Cantonese and English congregations do not often mix. In the smaller churches, they may have a joint service the first Sunday of the month for communion. The larger churches are not able to have a joint service because of space limitations. So when Christianity Today, a magazine read religiously by many Chinese pastors, presented a lead article on diversity entitled “All Churches Should Be Multicultural”, many Chinese American Christian leaders were puzzled.81 A typical Chinese church of one hundred persons may have four or five Caucasians in its English service. Caucasians are typically there because their spouses are Chinese. There may also be several Korean or Japanese young people in the youth group, who are invited by their good friends in high school. Interracially married couples involving a Chinese spouse usually attend white churches. Ways to welcome interracial couples in Chinese churches must be a topic of discussion and action for church leaders as more young adults are in interracial marriages. For example, the 1980 Census data indicate that about 15 percent of Chinese husbands and 16.8 percent of Chinese wives were married to non-Chinese, mainly whites.82 With a different sample, Sung found in 1990 that 27 percent of all marriages involving a Chinese American were interracial marriages.83

Fourth, Chinese American evangelicals split over the theological and social issues involving spiritual gifts. There are tensions over these issues whenever inter-group gatherings are held. The charismatic movement is growing among Chinese, and charismatic churches are among the largest of Chinese churches in the United States. Some pastors are accusing the charismatic groups of “stealing” their church members. Church members themselves show a lot of confusion in this area. A prominent pastor with a promising career was asked to resign from a large church for having charismatic leanings. The tension and the lack of communication and absolution over these issues are among the unhealthy signs of Chinese American evangelicalism.

Fifth, the Chinese American evangelicals are much divided regarding the Three-Self Patriotic Movement and its twin, the China Christian Council in China. Space does not allow a discussion of the government-sponsored Three-Self movement and its relationship to the well-known house churches, but it can be reported that feelings are strong among the leaders of Chinese American evangelicals. Many feel that, in order to help Christians and pastors in China, they must interact with Three-Self churches and their seminaries. Others feel that to work with the Three-Self people is a betrayal on the scale of Judas. They argue that Three-Self leaders are Communists, who are still persecuting Christians in the house church movement. Life long friendships have been broken, churches split, and family members divided over these differing opinions. Two of the most prominent churches in the west coast founded by the same person stopped cooperating with each other because one church works with House Church Christians and the other works with Three-Self people.

Sixth, Chinese American evangelicals are still looking for effective ways to meaningfully minister to the second generation. A prominent Chinese magazine devoted special attention in its July/August 2005 issue to address the “crisis” that nearly 50% of the young adults from Christian homes stopped going to church when they moved away to college. The magazine attributes the lack of programs, workers, language expertise, tolerant attitude, and cultural understanding on the part of the first generation leadership as causes.84 In the last twenty years, Chinese American churches with English-speaking programs for their children and youth have increased. Many also have contemporary English Sunday services for their high school and college students. Greater emphasis and financial investment must be made to their English ministries. Perhaps the leaders in Chinese Christian churches need to treat their English-speaking congregations as a viable part of their churches covering the whole life span instead of offering special programs only for their young people. If the “fifty percent” that the magazine is reporting is accurate, it is indeed a crisis.

And seventh, Chinese American evangelicals share a “dysfunction” in their churches that is not easy to address. The out-spoken veteran Christian journalist, Elisha Wu writes that there is “a serious illness peculiar to Chinese churches in North America- the conflicted relationship between employers (church officers) and employees (pastors).” 85 Wu describes how some pastors are abused by lay church leaders who hold high positions in American corporations, universities and businesses. Many of these successful professionals are very aggressive in insisting that churches be governed their way. Most Chinese pastors are not in a strong enough position to counteract these powerful laypeople and are frequently rendered ineffective. Wu calls this phenomenon within the North American Chinese churches “Amateurs Managing the Professionals.” The conflict with lay leaders (the amateurs) often leaves many Chinese pastors (the professionals) unemployed and a good number of pulpits in Chinese American churches vacant.

The past and the present in Chinese American churches have been examined. These churches are not monolithic, to be sure, but the main current of Chinese American evangelicalism can clearly be seen. These Christians have come a long way in light of early discriminative social pressures and the personal stresses that accompany people in Diaspora, but they have overcome. These evangelicals have also kept the faith. They do have many conflicts and challenges facing them. But what is their future? To borrow a saying attributed to Adoniram Judson, the first American missionary to the foreign shores, these Chinese American evangelicals believe the “future is as bright as the promise of God.”

References

1. C.E. Chapman, A History of California: The Spanish Period (New York: Macmillan, 1939), 8.

2. H.H. Bancroft, History of California (San Francisco: The History Company, 1890), VII, 335.

3. E.S. Meany, History of the State of Washington (New York: Macmillan. 1924), 26.

4. Betty Lee Sung, The Story of the Chinese in America: Their Struggle for Survival, Acceptance, and Full Participation in American Life- from the Gold Rush Days to the Present (New York: Macmillan, 1967). Leigh Bristo-Kagan, “Chinese Migration to California, 1851-1882: Selected Industries of Work, the Chinese Institutions and the Legislative Exclusion of a Temporary Work Force,” Ph.D. Dissertation in history and East Asian languages, Harvard University, 1982. Peter The New Chinatown (New York: The Noonday Press, 1987). Iris Chang, The Chinese in America: A Narrative History (New York: Penguin Books, 2003). Bill Ong Hing, Making and Remaking Asian America through Immigration Policy, 1850-1990 (Stanford: Stanford University Press).

5. Chinese American Data Center (http://members.aol.com/cheneseuse/ootre.htm). 2000 Census fact sheet.

6. Frederic Wakeman, The Strangers at the Gate: Social Disorder in South China, 1839-1861 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966), 3-9.

7. Mary R. Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York: Henry Holt, 1909), 497.

8. Ibid, 498.

9. Iris Chang, 132.

10. The Puritans and northern Europeans came to America first and established an American national identity with strong Anglo-American and European-American characteristics. Later immigrants from Italy and Ireland might have come with purely economic reasons just like Chinese laborers, but their similar European appearance made it easier for them to participate in the “Melting Pot” experiment. Even today, without any language and cultural difference, American-Born Chinese (ABC’s) of third or fourth generation continue to be viewed as foreigners. See, for example, Mia Tuan, Forever Foreigners or Honorary Whites? The Asian Ethnic Experience Today (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1998), 4. It is reasonable to assume that early Chinese laborers, with their strange language and customs, would experience far greater rejection in American society. See Stuart Creighton Miller, The Unwelcome Immigrant: The American Image of the Chinese, 1785-1882 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969).

11. This classic quote is taken from Richard Hofstader, William Miller, and Daniel Aaron, The American Republic (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1959), II, 187. Vivid pictures of hardship endured by early Chinese laborers could be seen in Madeline Y. Hsu, Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration between the United States and South China, 1882-1943 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000), 38; and David Howard Bain, Empire Express: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad (New York: Viking Press, 1999), 208, 639.

12. Betty Lee Sung, 41-43.

13. Iris Chang, 133-134.

14. Elmer Clarence Sandmeyer, The Anti-Chinese Movement in California (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 97.

15. Betty Lee Sung, 52.

16. Sandy Lydon, Chinese Gold: The Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region (Capitola, CA: Capitola Book, 1985), 117-118.

17. For a discussion of its long-term implications on the life and work of immigrant Chinese families, see Iris Chang, 135-138, 144-147; and case studies by Paul Siu, The Chinese Laundryman: a Study in Social Isolation (New York: New York University Press, 1987). For better understanding of effects of entry and re-try difficulties on the individuals and their families, see Him Mark Lai, Genny Lim, and July Yung, Island: Poetry and History of Chinese Immigrants on Angel Island, 1910-1940 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991) and Theodore T. Y. Hsieh, “Searching for Root on Angel Island”, Chinese American News (Chicago), August 12, 1994, 8. (In Chinese)

18. F.W. Riggs, Pressure on Congress: A Study of the Repeal of Chinese Exclusion (New York: King’s Crown Press, 1950). Roger Daniels, Guarding the Golden

Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004).

19. John Dollard, Leonard W. Doob, Neal E. Miller, O.H. Mowrer and Robert R. Sears, Frustration and Aggression (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1939), 1. In his discussion of race relations, anthropologist Francis Hsu attributed “insecurity” as cause of racial tension. Francis L. K. Hsu, Americans and Chinese: Reflections on Two Cultures and Their People (New York: American Museum Science Books, 1972).

20. Stuart Creighton Miller, 11.

21. Philip P. Choy, Lorraine Dong and Marlon K. Hom, The Coming Man: 19th Century American Perceptions of the Chinese (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994).

22. Ibid, 20-22.

23. Stuart Creighton Miller, 159-193.

24. Victor Nee and Brett de Barry Nee, Longtime Californ: a Documentary Study of an American Chinatown (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973).

25. Stuart Creighton Miller, 3.

26. For a history of organization and influences of “Tongs” in America, see Peter Kwong, The New Chinatown (New York: Noonday Press, 1987), 97-99, 112-114, 127-129; Iris Chang, 80-85, 204-205; and Richard H. Dillon, The Hatchet Men: The Story of the Tong Wars in San Francisco’s Chinatown (Sausalito, CA: A Comstock Editions, 1962). For a popular but realistic recent treatment of tong wars, see Robert Daley, Year of the Dragon (New York: Simon and Shuster, 1981) and Dan Mahoney, The Two Chinatowns (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001).

27. Peter Kwong, 107-123.

28. Betty Lee Sung, 214-232.

29. Ibid, 23-40.

30. E.R. Cayton and A.O. Liverly, The Chinese in the United States and the Chinese Christian Churches (New York: National Council of Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., 1955), 36-45.

31. Ibid, 46.

32. Theodore Tin-Yee Hsieh, The Chinese and the Chinese Church in Chicago: A Socio-Cultural Study of Their Missionary Implications. M.A. Thesis (Deerfield, IL: Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, 1968), 77.

33. Wesley Woo, Protestant Work Among the Chinese in San Francisco Area, 1850-1920. Ph.D. Dissertation (Berkeley, CA: Graduate Theological Union, 1983), 35-68.

34. E. R. Cayton and A. O. Liverly, 48.

35. Wesley Woo, 2.

36. Ibid, 100.

37. Theodore Tin-Yee Hsieh, “China—Past Mistakes and Present Dangers,” Evangelical Missions Quarterly, 16 (1980), 5-10.

38. Rose Hum Lee, The Chinese in the U.S.A. (Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press, 1960), 177.

39. Theodore Hsieh, 1980, 7.

40. John King Fairbank, ed. The Missionary Enterprises in China and America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974).

41. Theodore Hsieh, 1968, 68 & 79.

42. Silas Fung, A History of the Chinese Christian Union Church: 1890-1965 (Chicago: Chinese Christian Union Church, 1965)), 3-7; and Diamond Anniversary Commemorative Issue of the Chinese Christian Union Church of Chicago: 1915-1990 (Chicago: Chinese Christian Union Church, 1990).

43. Full quotation appeared in Lift up Your Eyes: Golden Jubilee of the Evangelical Free Church in South China, 12, cited in H. Wilber Norton, European Background and History of Evangelical Free Church Foreign Missions, 1887-1955 (Moline, IL: Christian Service Foundation, 1964), 89-90.

44. F. W. Riggs, 267.

45. Jonathan D. Spence, The Search for Modern China (New York: W. W. Norton, 1990), 654, 670-671. Iris Chang, 309-311.

46. Iris Chang, ix

47. See Betty Lee Sung, 93 and Iris Chang, 264-265. According Sung, there are seven classes that have priority of admission into the United States. These are unmarried children of U.S. citizens, spouses and unmarried children of permanent resident aliens, professionals and cultural persons, married children of U.S. citizens, brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens, skilled labor whose services are in great demand, and refugees. The arrivals of many new immigrants with education and wealth created a bipolar Chinese community in America, the poorer residents in Chinatown and the richer residents outside, as suggested by Iris Chang, x.

48. Iris Chang, 261-168.

49. Ibid, 328.

50. Peter Kwong, 3-5.

51. See Iris Chang, x. Also for an interesting contrast of life style between labor and student immigrant families, see Ben Fong-Torres, The Rice Room: Growing Up Chinese-American from Number Two Son to Rock ‘N” Roll (New York: A Plume Book by Penguin Group, 1995) and Pang-Mei Natasha Chang, Bound Feet & Western Dress (New York: Doubleday, 1996). Fong-Torres grew up in a Cantonese family of restaurant owner in Oakland’s Chinatown in the 1940’s and Chang grew up in a Mandarin home of a college professor on the campus of Yale University in the 1960’s.

52. Ibid, 108.

53. This change has to do with the shifting Cantonese/Non-Cantonese composition within the Chinese American community, having more and more Mandarin-speaking new immigrants from China in recent years. In addition, many Cantonese-speaking people are learning to speak Mandarin for practical, commercial and social reasons, but very few Mandarin-speaking people are learning to speak Cantonese in community at large. The churches reflect this change in the community.

54. New churches were established at an unusual rate in the 1960’s and 1970’s compared to the 1950’s and before. For example, in the six-county San Francisco Bay Area (San Francisco, San Mateo, Contra Costa, Alameda and Santo Clara) there was a total 16 churches between 1853 and 1950. Three new churches were started in the 1950’s. But there were 13 and 27 new churches started in the 1960’s and 1970’s, respectively. See James Chuck, An Exploratory Study of the Growth of Chinese Protestant Congregations from 1950 to Mid-1996 in Five Bay Area Counties (A research report of the Bay Area Chinese Churches Research Project, 2005, asianamereicancenter.org). This difference cannot be attributed to biological growth. There must be a large proportion of Christians among the new immigrants from Hong Kong during this period of immigration policy changes that created this growth in number. Similar phenomenon existed in Vancouver, Toronto, New York and Los Angeles where large number of Hong Kong immigrants went. We also saw the beginnings of many key denominational efforts to start new churches by Christian and Missionary Alliance Church and the Southern Baptist Convention in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Key para-church ministries such as Ambassadors for Christ, Inc.(AFC) and Chinese Christian Mission (CCM) were also organized in the 1960”s. Almost all the founding pastors of these new churches and the two founders (Ted Choy and Thomas Wang) of AFC and CCM came from Hong Kong or had gone through Hong Kong.

55. Cumberland Presbyterian Chinese Church: Celebrating 100 Years of Ministry, 1894-1994. Chinese version, 7.

56. This account is taken from Silas Fung, A History of the Chinese Christian Union Church of Chicago, 1890 to 1965 (Chicago: Chinese Christian Union Church, 1965), 21-43; and a short reflection written by Elder Stephen Yeh, Sr. in the Diamond Commemorative Issue of the Chinese Christian Union Church of Chicago, 1915-1990 (Chicago: Chinese Christian Union Church, 1990), 5. It is interesting to note that Elder Yeh is a Mandarin-speaking “student” immigrant who has played a key role in every change and development of this Cantonese-speaking “labor” church in the last 50 years. This Cantonese-speaking “labor” church was also served by three Mandarin-speaking “student” immigrants while they were students at Wheaton College near Chicago: Andrew Song (1948), Moses Yu (1954) and John Pao (1959, while completing his Th.D. at Northern Baptist Theological Seminary after Wheaton). All three have played key roles in theological education in Hong Kong and North America, serving as long-time presidents of three different seminaries

57. Paul Szeto, ed., Higher Ground: Evangelize China Fellowship 50th Anniversary Jubilee Celebration (Monterey Park, CA.: Evangelize China Fellowship, Inc., 1997). Andrew Gih was a gifted preacher and fund-raiser, moving hundreds of young people into full-time ministry and supporting thousands of orphans in both Hong Kong and Indonesia. Typically, the Evangelize China Fellowship-established churches are named Canaan Churches.

58. Zeng Gengrong, Zhao Junying Boshi Zongjiaoguan Zhi Tantao (A Study of the Religious View of Dr. Calvin Chao) (Rosemead, CA: Chinese For Christ Theological Seminary, 1993). Considered by many as a Christian intellectual, Calvin Chao published several book-length critiques of communism in general and Chinese communists in particular from a Christian perspective. He was not a welcome figure in mainland China. See Philip Yuen-Sang Leung, Chinese Fundamentalism in Modern Chinese: Calvin Chao and the “Chinese For Christ” Movement (Hong Kong: Alliance Bible Seminary, 2002). (http:www.cuhk.edu.hk/his/2002/chi/staff/leung/confu_christ/christ04.htm).

59. See Christian Witness Theological Seminary Academic Catalogue (Concord, CA: Christian Witness Theological Seminary, 2004-2006), 3. As its president for the first twenty years, Moses Yu used a very unique teaching style by traveling regularly across the country with bands of students preaching and evangelizing. Graduates then planted churches on their own. For example, in Missouri, the Christian Witness Center (www.cwcnet.org) is having a thriving ministry on various college campuses in the Mid-west and in New York City, the Faith Bible Institute, started by two graduates, has seen its impact grow in recent years. His own Hymnody and Bible House, located in Berkeley, California, is almost running by itself based on reputation alone. See also Moses LeeKung Yu, Ya-Jin Tien-Ming (Night-Ending Sky-Brightening), (P.O. Box 903, Berkeley, CA 94701). This autobiographical account offers an interesting history of Yu’s perspectives and relationships with several key figures and about some key events among the evangelicals in China between 1930 and 1949. These important persons and key events were formative of the mind-set of Chinese American evangelicals today.

60. Fenggang Yang, Chinese Christians in America: Conversion, Assimilation, and Adhesive Identities (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999).

61. See Thomas Wang, ed., America, Return to God (Sunnyvale, CA: Great Commission Center International, 2006), inside back cover page.

62. Evelyn Nakno Glenn and Stacey G.H. Yap, Chinese American Families. In Ronal L. Taylor, ed., Minority Families in the United States: A Multicultural Perspective (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998), 133.

63. The language debates seem to have disappeared in recent years. Perhaps it is due to the increasing comfort of using separate services and multiple staff. Many churches with less than one hundred members are having worship services in English and in Mandarin or Cantonese. Larger churches begin to have services in all three languages and employ a pastor for each. Cumberland Presbyterian Chinese Church in San Francisco, Bay Area Chinese Bible Church in San Leandro, and Chinese Christian Union Church in Chicago, for example, have literately three separate churches based on language “under one roof.”